|< C & C++ Preprocessor Directives 1 |Main | C & C++ Type Specifiers >|Site Index |Download |

MODULE 10

THE C/C++ PREPROCESSOR DIRECTIVES 2: #define etc.

My Training Period: hours

The C/C++ preprocessor directives programming skills that should be acquired:

-

Able to understand and use #error,#pragma,# and ## operators and #line.

-

Able to display error messages during conditional compilation.

-

Able to understand and use assertions.

|

| 10.6 The #error And #pragma Preprocessor Directive

#error tokens

#if (MyVAL != 2 && MyVAL != 3) #error MyVAL must be defined to either 2 or 3 #endif

// the #error directive... #include <stdio.h>

#if MyVAL != 2 #error MyVAL must be defined to 2 #endif

int main() { return 0; } // no output, error message during the compilation

Error: test.cpp(7,1):Error directive: MyVAL must be defined to 2

|

Then correct the error by defining MyVal to2 as the following program and when you rebuild, it should be OK.

// the #error directive...

#include <stdio.h>

#defineMyVAL 2

#if MyVAL != 2

#error MyVAL must be defined to 2

#endif

int main()

{

return 0;

}

// no output when running, no error when compiling

Another simple program example.

// another #error directive example

#include <stdio.h>

#if MyChar != 'X'

#error The MyChar character is not 'X'

#endif

int main()

{

return 0;

}

// no output, with error message during the compilation

Error something like the following should be expected.

Error: test.cpp(6, 1):Error directive: The MyChar character is not 'X'

The#pragma directive takes the following form,

#pragma tokens

Thetokens are a series of characters that gives a specific compiler instruction and arguments, if any and causes an implementation-defined action. A pragma not recognized by the implementation is ignored without any error or warning message.

Apragma is a compiler directive that allows you to provide additional information to the compiler. This information can change compilation details that are not otherwise under your control. For more information on #error and#pragma, see the documentation of your compiler.

Keywordpragma is part of the C++ standard, but the form, content, and meaning of pragma is different for every compiler.

This means different compilers will have different pragma directives.

No pragma are defined by the C++ standard. Code that depends on pragma is not portable. It is normally used during debugging process.

For example, Borland's #pragma message has two forms:

#pragma message ("text" ["text"["text" ...]])

#pragma message text

It is used to specify a user-defined message within your program code.

The first form requires that the text consist of one or more string constants, and the message must be enclosed in parentheses.

The second form uses the text following the #pragma for the text of the warning message. With both forms of the#pragma, any macro references are expanded before the message is displayed.

The following program example will display compiler version of the Borland C++ if compiled with Borland C++ otherwise will display "This compiler is not Borland C++" message and other predefined macros.

// the #pragma directive...

#include <stdio.h>

// displays either "You are compiling using

// version xxx of BC++" (where xxx is the version number)

// or "This compiler is not Borland C++", date, time

// console or not... by using several related

// predefined macro such as __DATE__ etc

#ifdef __BORLANDC__

#pragma message You are compiling using Borland C++ version __BORLANDC__.

#else

#pragma message ("This compiler is not Borland C++")

#endif

#pragma message time: __TIME__.

#pragma message date: __DATE__.

#pragma message Console: __CONSOLE__.

int main()

{

return 0;

}

// no output

The following message should be generated if compiled with Borland C++.

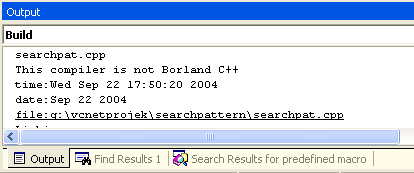

Program example compiled with VC++/VC++ .Net.

// #pragma directive...

#include <stdio.h>

// displays either "You are compiling using

// version xxx of BC++" (where xxx is the version number)

// or "This compiler is not Borland C++", date, time

// console or not... by using several related

// predefined macro such as __DATE__ etc

#ifdef __BORLANDC__

#pragmamessage You are compilingusing Borland C++ version __BORLANDC__.

#else

#pragmamessage ("This compiler is not Borland C++")

#endif

#pragmamessage ("time:" __TIMESTAMP__)

#pragmamessage ("date:" __DATE__)

#pragmamessage ("file:" __FILE__)

int main()

{

return 0;

}

Another program example compiled using VC++/VC++ .Net

// #pragma directives...

#include <stdio.h>

#if _M_IX86 != 500

#pragma message("Non Pentium processor build")

#endif

#if _M_IX86 == 600

#pragmamessage("but Pentium II above processor build")

#endif

#pragmamessage("Compiling " __FILE__)

#pragmamessage("Last modified on " __TIMESTAMP__)

int main()

{

return 0;

}

The following message should be expected.

So now, you know how to use the #pragmas. For other#pragmas, please check your compiler documentations and also the standard of theISO/IEC C/C++ for any updates.

10.7 The # And ## Operators

The# and ## preprocessor operators are available in ANSI C. The # operator causes a replacement text token to be converted to a string surrounded by double quotes as explained before.

Consider the following macro definition:

#define HELLO(x) printf("Hello, " #x "\n");

WhenHELLO(John) appears in a program file, it is expanded to:

printf("Hello, ""John" "\n");

The string "John" replaces #x in the replacement text. Strings separated by white space are concatenated during preprocessing, so the above statement is equivalent to:

printf("Hello, John\n");

Note that the# operator must be used in a macro with arguments because the operand of # refers to an argument of the macro.

The## operator concatenates two tokens. Consider the following macro definition,

#define CAT(p, q) p ## q

WhenCAT appears in the program, its arguments are concatenated and used to replace the macro. For example,CAT(O,K) is replaced byOK in the program. The## operator must have two operands.

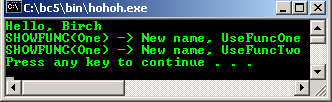

A program example:

#include <stdio.h>

#define HELLO(x) printf("Hello, " #x "\n");

#define SHOWFUNC(x) Use ## Func ## x

int main(void)

{

// new concatenated identifier, UseFuncOne

char * SHOWFUNC(One);

// new concatenated identifier, UseFuncTwo

char * SHOWFUNC(Two);

SHOWFUNC(One) = "New name, UseFuncOne";

SHOWFUNC(Two) = "New name, UseFuncTwo";

HELLO(Birch);

printf("SHOWFUNC(One) -> %s \n",SHOWFUNC(One));

printf("SHOWFUNC(One) -> %s \n",SHOWFUNC(Two));

return 0;

}

Output:

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

10.8 Line Numbers

The#line preprocessor directive causes the subsequent source code lines to be renumbered starting with the specified constant integer value. The directive:

#line 100

Starts line numbering from 100 beginning with the next source code line. A file name can be included in the#line directive. The directive:

#line 100 "file123.cpp"

Indicates that lines are numbered from 100 beginning with the next source code line, and that the name of the file for purpose of any compiler messages is "file123.cpp".

The directive is normally used to help make the messages produced by syntax errors and compiler warnings more meaningful. The line numbers do not appear in the source file.

10.9 Predefined Macros

There are standard predefined macros as shown in Table 10.1. The identifiers for each of the predefined macros begin and end with two underscores. These identifiers and the defined identifier cannot be used in#define or #undef directive.

There are more predefined macros extensions that are non standard, compilers specific, please check your compiler documentation. The standard macros are available with the same meanings regardless of the machine or operating system your compiler installed on.

Symbolic Constant | Explanation |

__DATE__ | The date the source file is compiled (a string of the form "mmm dd yyyy" such as "Jan 19 1999"). |

__LINE__ | The line number of the current source code line (an integer constant). |

__FILE__ | The presumed names of the source file (a string). |

__TIME__ | The time the source file is compiled (a string literal of the form :hh:mm:ss). |

__STDC__ | The integer constant 1. This is intended to indicate that the implementation is ANSI C compliant. |

Table 10.1: The predefined macros. | |

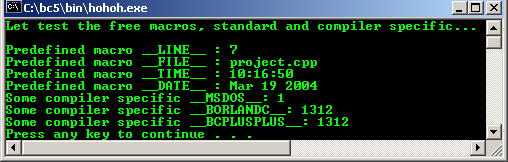

A program example:

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int main(void)

{

cout<<"Let test the free macros, standard and compiler specific..."<<endl;

cout<<"\nPredefined macro __LINE__ : "<<__LINE__<<endl;

cout<<"Predefined macro __FILE__ : "<<__FILE__<<endl;

cout<<"Predefined macro __TIME__ : "<<__TIME__<<endl;

cout<<"Predefined macro __DATE__ : "<<__DATE__<<endl;

cout<<"Some compiler specific __MSDOS__: "<<__MSDOS__<<endl;

cout<<"Some compiler specific __BORLANDC__: "<<__BORLANDC__<<endl;

cout<<"Some compiler specific __BCPLUSPLUS__: "<<__BCPLUSPLUS__<<endl;

return 0;

}

Output:

10.10 Assertions

assert(q <= 100);

|

Thus, when assertions are no longer needed, the line:

#define NDEBUG

Is inserted in the program file rather than deleting each assertion manually.

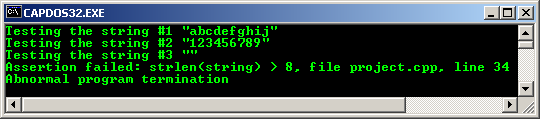

A program example:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <assert.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

void TestString(char *string);

void main()

{

// first test array of char, 10 characters...

// should be OK for the 3 test conditions...

char test1[ ] = "abcdefghij";

// second test pointer to string, 9 characters...

// should be OK for the 3 test conditions...

char *test2 = "123456789";

// third test array char, empty...

// should fail on the 3rd condition, cannot be empty...

char test3[ ] = "";

printf("Testing the string #1 \"%s\"\n", test1);

TestString(test1);

printf("Testing the string #2 \"%s\"\n", test2);

TestString(test2);

printf("Testing the string #3 \"%s\"\n", test3);

TestString(test3);

}

void TestString(char * string)

{

// set the test conditions...

// string must more than 8 characters...

assert(strlen(string) > 8);

// string cannot be NULL

assert(string != NULL);

// string cannot be empty....

// test3 should fail here and program abort...

assert(string != '\0');

}

Output:

You can see from the output, project.cpp is__FILE__ and line 34 is__LINE__ predefined macros defined inassert.h file as shown in the source file at the end of this Module.

For this program example, let try invoking the Borland® C++ Turbo Debugger. The steps are:

Click Tool menu → Select Turbo Debugger sub menu → Press Alt + R (Run menu) → Select Trace Into or press F7 key continuously until program terminate (line by line code execution) → When small program dialog box appears, press Enter/Return key (OK) → Finally, press Alt+F5 to see the output window.

Figure 10.1: Borland Turbo® Debugger window.

For debugging using Microsoft Visual C++ or .Net readDebugging your C/C++ programs. For Linux using gdb, readDebugging C/C++ programs using Linux GDB.

Another program example.

// assert macro and DEBUG, NDEBUG

// NDEBUG will disable assert().

// DEBUG will enable assert().

#define DEBUG

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

#include <assert.h>

int main()

{

int x, y;

// tell user if NDEBUG is defined and do assert.

#if defined(NDEBUG)

cout<<"NDEBUG is defined. Assert disabled,\n";

#else

cout<<"NDEBUG is not defined. Assert enabled.\n";

#endif

// prompt user some test data...

cout<<"Insert two integers: ";

cin>>x>>y;

cout<<"Do the assert(x < y)\n";

// if x < y, it is OK, else this program will terminate...

assert(x < y);

if(x<y)

{

cout<<"Assertion not invoked because "<<x<<" < "<<y<<endl;

cout<<"Try key in x > y, assertion will be invoked!"<<endl;

}

else

cout<<"Assertion invoked, program terminated!"<<endl;

return 0;

}

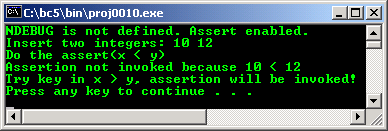

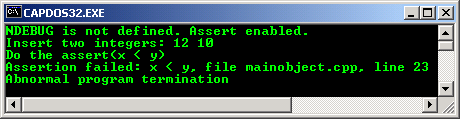

Normal Output:

Abnormal program termination output:

If you use Microsoft Visual Studio® 6.0/2005, the output should be more informative with dialog box displayed whether you want to abort, retry or ignore :o) as shown below.

And the output screen tries to tell you something as shown below.

The following program example compiled usingg++. For the gdb debugger, please readUsing gcc, gdb, g++ and gas on Linux.

//////// testassert.cpp /////////

// DEBUG will enable assert().

#define DEBUG

#include <iostream>

#include <cassert>

using namespace std;

int main()

{

int x, y;

// tell user if NDEBUG is defined and do assert.

#if defined(NDEBUG)

cout<<"NDEBUG is defined. Assert disabled,\n";

#else

cout<<"NDEBUG is not defined. Assert enabled.\n";

#endif

// prompt user some test data...

cout<<"Insert two integers: ";

cin>>x>>y;

cout<<"Do the assert(x < y)\n";

// if x < y, it is OK, else this program will terminate...

assert(x < y);

if(x<y)

{

cout<<"Assertion not invoked because "<<x<<" < "<<y<<endl;

cout<<"Try key in x > y, assertion will be invoked!"<<endl;

}

else

cout<<"Assertion invoked, program terminated!"<<endl;

return 0;

}

[bodo@bakawali ~]$ g++ testassert.cpp -o testassert

[bodo@bakawali ~]$ ./testassert

NDEBUG is not defined. Assert enabled.

Insert two integers: 30 20

Do the assert(x < y)

testassert: testassert.cpp:24: int main(): Assertion `x < y' failed.

Aborted

[bodo@bakawali ~]$ ./testassert

NDEBUG is not defined. Assert enabled.

Insert two integers: 20 30

Do the assert(x < y)

Assertion not invoked because 20 < 30

Try key in x > y, assertion will be invoked!

----------------------------------------------------Note--------------------------------------------------

Program Sample

The following program sample is the assert.h header file. You can see that many preprocessor directives being used here.

/* assert.h

assert macro

*/

/*

* C/C++ Run Time Library - Version 8.0

*

* Copyright (c) 1987, 1997 by Borland International

* All Rights Reserved.

*

*/

/* $Revision: 8.1 $ */

#if !defined(___DEFS_H)

#include <_defs.h>

#endif

#if !defined(RC_INVOKED)

#if defined(__STDC__)

#pragma warn -nak

#endif

#endif /* !RC_INVOKED */

#if !defined(__FLAT__)

#ifdef __cplusplus

extern "C" {

#endif

void _Cdecl _FARFUNC __assertfail( char _FAR *__msg,

char _FAR *__cond,

char _FAR *__file,

int __line);

#ifdef __cplusplus

}

#endif

#undef assert

#ifdef NDEBUG

# define assert(p) ((void)0)

#else

# if defined(_Windows) && !defined(__DPMI16__)

# define _ENDL

# else

# define _ENDL "\n"

# endif

# define assert(p) ((p) ? (void)0 : (void) __assertfail( \

"Assertion failed: %s, file %s, line %d" _ENDL, \

#p, __FILE__, __LINE__ ) )

#endif

#else /* defined __FLAT__ */

#ifdef __cplusplus

extern "C" {

#endif

void _RTLENTRY _EXPFUNC _assert(char * __cond, char * __file, int __line);

/* Obsolete interface: __msg should be "Assertion failed: %s, file %s, line %d"

*/

void _RTLENTRY _EXPFUNC __assertfail(char * __msg, char * __cond, char * __file, int __line);

#ifdef __cplusplus

}

#endif

#undef assert

#ifdef NDEBUG

#define assert(p) ((void)0)

#else

#define assert(p) ((p) ? (void)0 : _assert(#p, __FILE__, __LINE__))

#endif

#endif /* __FLAT__ */

#if !defined(RC_INVOKED)

#if defined(__STDC__)

#pragma warn .nak

#endif

#endif /* !RC_INVOKED */

Further related preprocessor directives reading and digging:

- A complete process involved during the preprocessing, compiling and linking can be read inC/C++ - Compile, link and running programs.

- Check the best selling C / C++ books at Amazon.com.