|< C++ STL Algorithm 15 | Main | C Linux Socket Programming Tutorial 1 >|Site Index |Download |

MODULE 38

THE C++ STL FUNCTION OBJECT & MISC

My Training Period: xx hours

This is a final part of theC++ Standard Template Library (STL) programming tutorial series. C++ codes samples of the member functions compiled using MicrosoftVisual C++ .Net, win32 empty console mode application. Source code is available inC++ function object source code samples. You can proceed toLinux Socket programming using GNU C or you can go back to theTenouk.com main page for more C & C++ programming tutorials. Have a nice coding!

|

| The C++ STL function object skills that supposed to be acquired:

What do we have in this page?

38.1 Function Objects

function(arg1, arg2); // a function call

class XYZ { public: // define "function call" operator return-value operator() (arguments) const; ... };

XYZ foo; ... // call operator() for function object foo foo(arg1, arg2);

// call operator() for function object foo foo.operator() (arg1, arg2);

|

// function object example

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <algorithm>

using namespace std;

// a simple function object that prints the passed argument

class PrintSomething

{

public:

void operator() (int elem) const

{ cout<<elem<<' '; }

};

int main()

{

vector<int> vec;

// insert elements from 1 to 10

for(int i=1; i<=10; ++i)

vec.push_back(i);

// print all elements

for_each (vec.begin(), vec.end(), //range

PrintSomething()); //operation

cout<<endl;

}

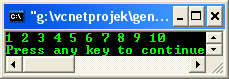

Output:

The classPrintSomething() defines objects for which you can call operator() with an int argument.

The expression:

PrintSomething()

In the statement

for_each(vec.begin(), vec.end(),

PrintSomething());

Creates a temporary object of this class, which is passed to the for_each() algorithm as an argument. The for_each() algorithm is written like this:

namespace std

{

template <class Iterator, class Operation>Operation for_each(Iterator act, Iterator end, Operation op)

{

while(act != end)

{ // as long as not reached the end

op(*act); // call op() for actual element

act++; // move iterator to the next element

}

return op;

}

}

for_each() uses the temporary function objectop to call op(*act) for each element act. If the third parameter is an ordinary function, it simply calls it with *act as an argument.

If the third parameter is a function object, it calls operator() for the function object op with *act as an argument. Thus, in this example program for_each() calls:

PrintSomething::operator()(*act)

Function objects are more than functions, and they have some advantages:

38.2 Function objects are smart functions

Objects that behave like pointers are smart pointers. This is similarly true for objects that behave like functions: They can be smart functions because they may have abilities beyond operator(). Function objects may have other member functions and attributes.

This means that function objects have a state. In fact, the same function, represented by a function object, may have different states at the same time. This is not possible for ordinary functions.

Another advantage of function objects is that you can initialize them at runtime before you call them.

38.3 Each function object has its own type

Ordinary functions have different types only when their signatures differ. However, function objects can have different types even when their signatures are the same.

In fact, each functional behavior defined by a function object has its own type. This is a significant improvement for generic programming using templates because you can pass functional behavior as a template parameter.

It enables containers of different types to use the same kind of function object as a sorting criterion. This ensures that you don't assign, combine, or compare collections that have different sorting criteria. You can even design hierarchies of function objects so that you can, for example, have different, special kinds of one general criterion.

38.4 Function objects are usually faster than ordinary functions

The concept of templates usually allows better optimization because more details are defined at compile time. Thus, passing function objects instead of ordinary functions often results in better performance.

For example, suppose you want to add a certain value to all elements of a collection. If you know the value you want to add at compile time, you could use an ordinary function:

void add10 (int& elem)

{ elem += 10; }

void funct()

{

vector<int> vec;

...

for_each(vec.begin(), vec.end(), // range

add10); // operation

}

If you need different values that are known at compile time, you could use a template instead:

template <int theValue> void add(int& elem) { elem += theValue; }

void funct() { vector<int> vec; ... for_each (vec.begin(), vec.end(), // range add<10>);// operation }

|

// a function object example

#include <iostream>

#include <list>

#include <algorithm>

using namespace std;

// a function object that adds the value with which it is initialized

class AddValue

{

private:

// the value to add

int theValue;

public:

// constructor initializes the value to add

AddValue(int val) : theValue(val) { }

// the function call for the element adds the value

void operator() (int& elem) const

{ elem += theValue; }

};

int main()

{

list<int> lst1;

// the first call of for_each() adds 10 to each value:

for_each(lst1.begin(), lst1.end(), // range

AddValue(10));// operation

}

Here, the expressionAddValue(10) creates an object of typeAddValue that is initialized with the value10. The constructor ofAddValue stores this value as the membertheValue.

Insidefor_each(),"()" is called for each element of lst1. Again, this is a call of operator() for the passed temporary function object of type AddValue. The actual element is passed as an argument. The function object adds its value 10 to each element. The elements then have the following values: after adding 10: 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19

The second call of for_each() uses the same functionality to add the value of the first element to each element. It initializes a temporary function object of type AddValue with the first element of the collection:

AddValue (*lst1.begin())

The output is then as follows:

after adding first element: 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30

By using this technique, two different function objects can solve the problem of having a function with two states at the same time. For example, you could simply declare two function objects and use them independently:

AddValue addx (x); // function object that adds value x

AddValue addy (y); // function object that adds value y

for_each (vec.begin(), vec.end(), // add value x to each element

addx);

...

for_each (vec.begin(), vec.end(), // add value y to each element

addy);

...

for_each (vec.begin(), vec.end(), // add value x to each element

addx);

38.5 Predefined Function Objects

The C++ standard library contains several predefined function objects that cover fundamental operations. By using them, you don't have to write your own function objects in several cases.

A typical example is a function object used as a sorting criterion.

The default sorting criterion for operator< is the predefined sorting criterion less<>. Thus, if you declare:

set<int> st;

It is expanded to:

set<int, less<int> > st; // sort elements with <

From there, it is easy to sort elements in the opposite order:

set<int, greater<int> > st; // sort elements with >

Similarly, many function objects are provided to specify numeric processing. For example, the following statement negates all elements of a collection:

transform(vec.begin(), vec.end(), // source

vec.begin(),// destination

negate<int>());// operation

The expression:

negate<int>()

Creates a function object of the predefined template class negate that simply returns the negated element of type int for which it is called.

Thetransform() algorithm uses that operation to transform all elements of the first collection into the second collection. If source and destination are equal (as in this case), the returned negated elements overwrite themselves. Thus, the statement negates each element in the collection.

Similarly, you can process the square of all elements in a collection:

// process the square of all elements

transform(vec.begin(), vec.end(), // first source

vec.begin(),// second source

vec.begin(),// destination

multiplies<int>());// operation

Here, another form of the transform() algorithm combines elements of two collections by using the specified operation, and writes the resulting elements into the third collection.

Again, all collections are the same, so each element gets multiplied by itself, and the result overwrites the old value.

-------------------------------------------The real End for STL topics--------------------------------------

38.6 Miscellaneous

The following items may not be covered in details in this part of tutorial but you may have encountered them somewhere in the various program examples.

Class pair

Is provided to treat two values as a single unit. It is used in several places within the C++ standard library. In particular, the container classes’ map andmultimap use pairs to manage their elements, which are key/value pairs.

make_pair() template function

Enables you to create a value pair without writing the types explicitly.

Theauto_ptrtype

The auto_ptr type is provided by the C++ standard library as a kind of a smart pointer that helps to avoid resource leaks when exceptions are thrown.

Numeric types

In general it is platform-dependent limits. The C++ standard library provides these limits in the template numeric_limits. These numeric limits replace and supplement the ordinary preprocessor constants of C.

These constants are still available for integer types in<climits> and <limits.h>, and for floating-point types in <cfloat> and <float.h>.

The new concept of numeric limits has two advantages: First, it offers more type safety. Second, it enables a programmer to write templates that evaluate these limits. Take note that it is always better to write platform-independent code by using the minimum guaranteed precision of the types.

Others

The algorithm library, file<algorithm> header, includes three auxiliary functions, one each for the selection of the minimum and maximum of two values and one for the swapping of two values. These auxiliary functions have been used in various program examples in this tutorial. Four template functions define the comparisonoperators!=,>, <=, and >= by calling the operators == and <. These functions are defined in <utility>. Don’t forget other standard C++ header files such as <ios>,<locale>,<valarray>,<new>,<memory>,<complex> etc.

Further C++ related reading:

Source code is available inC++ function object source code samples.

Acomplete C++ Standard Library documentation that includes STL.